Below is a summary of insights on key drivers, risks and relevant factors in the U.S. financial sector, as well as case studies of three financial institutions: BlackRock, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Citigroup. While the findings focus on large U.S. financial institutions, please note that due to the international nature of large financial institutions (for example, while Goldman Sachs is an American bank, it is considered a global bank), some of the data presented in the findings has a global scope. However, only data that is relevant and applicable to U.S. financial institutions is used.

Table of Contents

INVESTOR PRESSURE

Pressure from investors come in many areas, from operation and performance to investment strategies. This section identifies two types of investor pressure: performance and social responsibility. As the financial sector is facing rising competition from other firms (discussed in the next section), investor pressure means financial institutions must act fast before losing investors to another industry.

1). Pressure on Performance

- According “The State of the Financial Industry 2020” by consulting firm Oliver Wyman, “the need to invest and build the firm of the future is pressing” while “the window to deliver is gradually closing.”

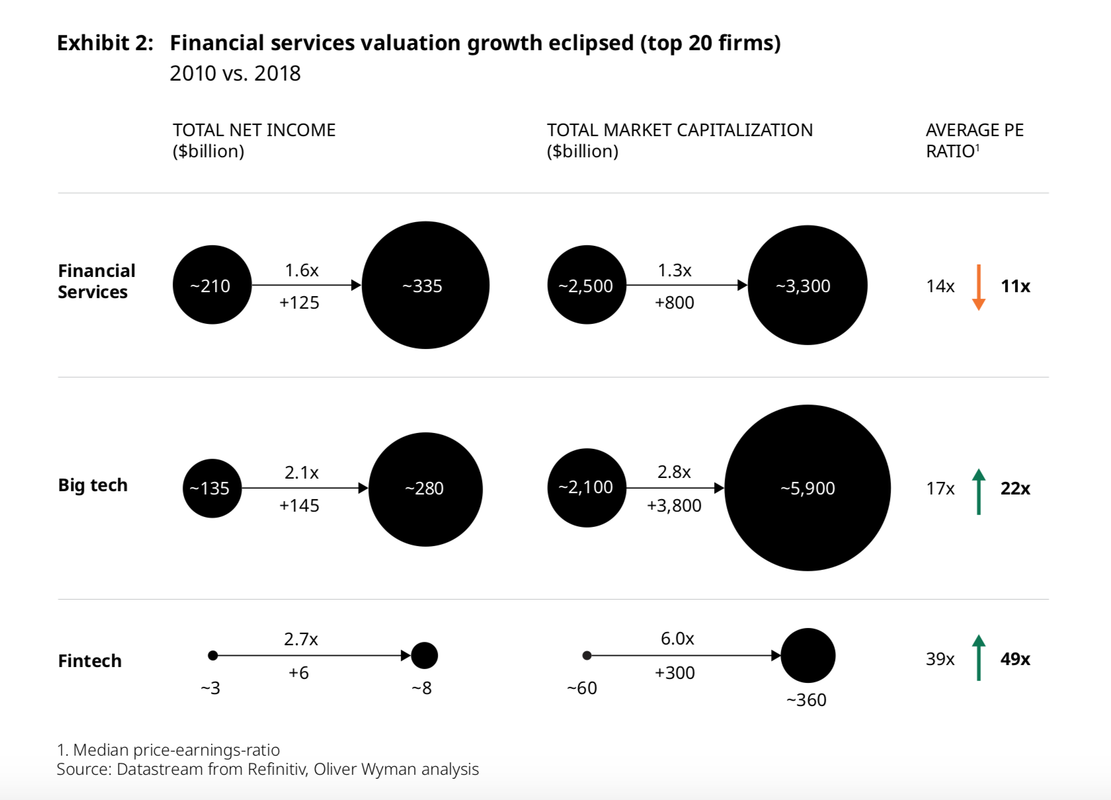

- The report finds that the price to earnings multiple in the financial services has fallen from 14 times to 11 times. Investors take note of this. In North America, cost-to-income ratio for banks decreased by 8 percentage points between 2010 and 2018. While this indicates a marginal improvement, progress on productivity is slow. Compared to the tech and fintech sectors, financial services are becoming less attractive for investors (see the figure below).

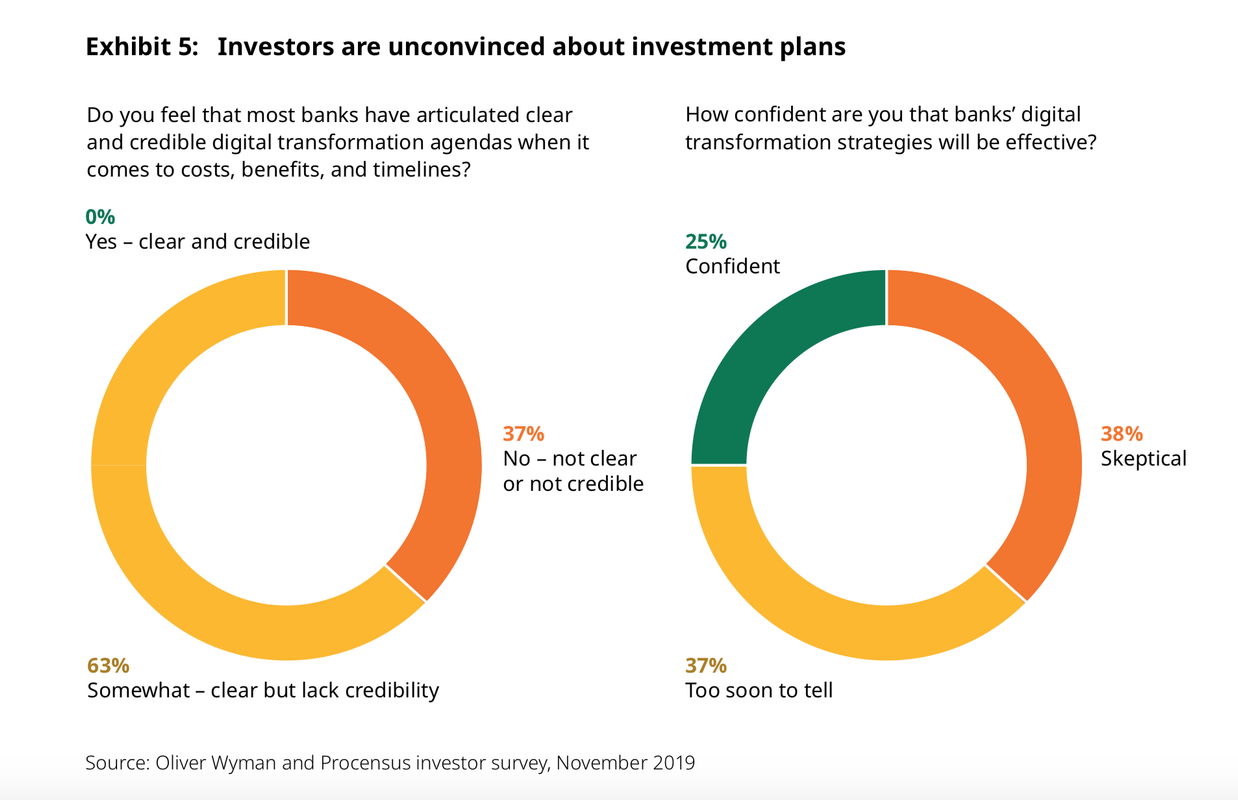

- Additionally, the report finds that investors are skeptical of change programs such as digital transformation introduced by financial institutions and do not feel that they understand what and why the firms are investing in these programs (see the figure below).

2). Pressure on Social Responsibility

- While many financial institutions around the world are increasingly focusing on environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) factors in their strategies in preparation for current or future regulations, the decisions to go deeper into ESG by American financial institutions are driven by market–i.e., investors.

- According to a study by Harvard Business Review (HBR), investors have become increasingly interested in ESG issues over the past several years. This is particularly true for investors in large financial firms as they view issues such as the environment to have impact on their long-term investment and liabilities. HBR details the other five factors driving investors to focus on ESG, from financial returns to changing view of fiduciary duty (details may be found here).

- The largest financial institutions have one way or other made some commitment to ESG. For instance, J.P. Morgan Chase “pledged $200 billion to wind farms and other sources of renewable energy.” Goldman Sachs announced spending of $750 billion on sustainable finance over the next decade. At the same time, Bank of America has announced $300 billion to sustainable investment.

- In the midst of the pandemic, it appears that ESG-related funds are losing less than their counterparts. In a Morningstar analysis of “responsible investment” funds, 70% of them outperformed their peers in the first quarter of 2020.

While some believe that the pressure to take part in socially responsible investment is driven by real concerns over social issues, data suggests that ESG tends to generate higher returns. This tends to be in the financial interest of the investors.

RISING COMPETITION FROM TECH COMPANIES

There is an increasingly blurring line between the financial services and the tech sector. Most notably many major financial institutions have started to identify themselves as tech hubs while many tech companies are expanding into financial services.

- “Almost a decade after the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, what keeps bankers awake at night is not regulation by Washington, but competition from Silicon Valley“–Dan Murphy in the Milken Institute Review.

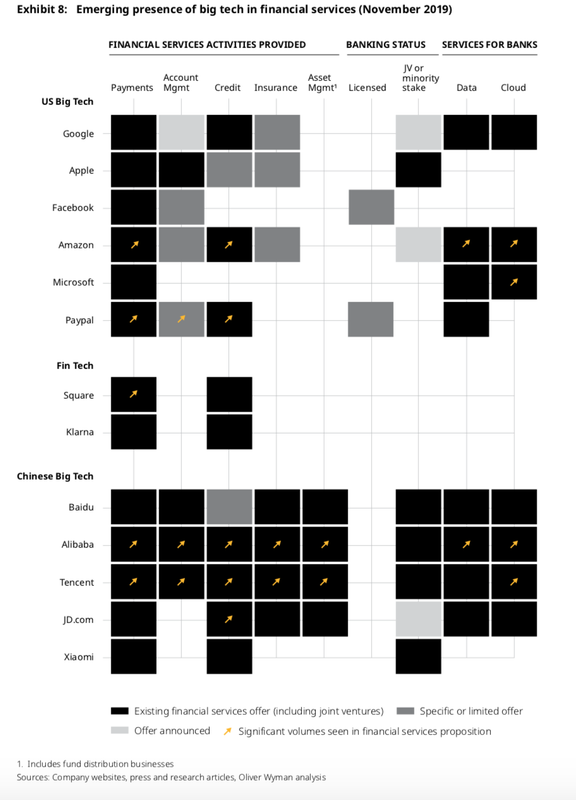

- From Google to Apple, big tech companies are pushing into the financial services while they are not regulated as banks (note that banks are among the most heavily regulated in the United States). Last year, Apple introduced Apple Card in partnership with Goldman Sachs while Google is planning to offer checking accounts in partnership with Citigroup and other financial institutions. Another example is the plan by Facebook to launch a digital currency Libra in as early as January next year after the previous version–backed by PayPal, Mastercard, Vodafone and eBay, all of whom have quit–was proven unsuccessful.

- As mentioned in the previous section, the largest tech companies have outperformed the largest financial firms over the past decade–average price to earnings ratio of 22 vs 11 as of 2018. All the U.S. tech companies are positioning themselves in financial services, according to Oliver Wyman. “With the big technology companies, there is little room for complacency. The size of these firms’ customer networks and ‘data gravity’ can pull apart entire industries.”

- Oliver Wyman argues that it is a three-way match among the financial firms, fintech, and tech companies. Financial firms tend to treat fintech startups as “participants in their innovation labs and accelerators.” However, Oliver Wyman refers to the threat as “death by a thousand cuts as much as disruption, with newcomers cherry-picking profitable activity and eroding margins.”

- Additionally, many major financial institutions have collaborated with tech companies as in examples above and many more. The appeal of such collaborations for financial institutions is the mass networks of tech companies which could bring in a massive number of new clients overnight–something that normally takes financial institutions decades to build. At the same time, financial firms must avoid becoming a “dumb utility.” As a result, they are caught between partnership and defense. Please note that competition from U.S. big tech and fintech is mostly in payments, not in asset management (see the figure below). Thus, the threats are mostly to banks and less on investment management firms such as BlackRock.

- A report by the Financial Stability Board, an international regulatory group, suggests that competition from big tech could lead to reduced resilience of financial institutions “either by affecting their profitability or by reducing the stability of their funding. BigTech firms’ widespread access to valuable customer data could also be self-reinforcing via network effects.” The report also suggests that the partnerships between big tech and financial institutions may also pose risks if risk management and controls of big tech companies are less effective than those of financial institutions, which are regulated.

- Large financial institutions have also aggressively invested in innovation–although investors do not yet have full confidence in such investment (see the previous section)–to keep themselves relevant in the increasingly technologically-driven world. For example, J.P. Morgan Chase invests $11 billion a year in technology with a team of 50,000 technologists. The bank claims that “JPMorgan Chase is in the midst of a once-in-a-generation transformation” into the disruptor technology. It claims that what differentiates the bank from tech companies is its ability to invest in a broad number of technologies simultaneously.

- Nonetheless, the only barriers to entry for big tech are regulatory, not commercial or technological.

COVID-19 IMPACTS AND FINANCIAL RESILIENCE

Like other sectors, the financial services sector has been hit by the lockdowns of the economy as a result of the pandemic. The sector is also impacted in a number of other ways, such as credit, market and liquidity risks. As suggested in the initial findings, there have been rises in loan losses, which are still lower than the levels seen in the last financial crisis. This section looks at the impacts of COVID-19 and the resiliency of the U.S. financial institutions to absorb losses in the crisis.

- A staff report by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) identifies three key COVID-induced stresses on the financial system: short-term funding stresses, market structure/liquidity driven stresses, and long-term credit stresses.

- Short-term funding stresses: The SEC report finds that the short-term funding market (STFM) “experienced significant stress in March 2020 almost immediately following the inception of the COVID-19 economic shock.” Market prices of equity and debt securities quickly dropped while yields and asset-price volatility rose, leading to higher funding costs in STFM. The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank intervened in mid-March to restore confidence and lower interest rates, “resulting in increased liquidity, tighter spreads, and funding costs in line with historical norms.”

- Market structure/liquidity stresses: In March and April, the average daily trading volumes for corporate bonds in March and April increased by approximately 48% (the unusually high volumes indicate market panic), compared to the preceding two years, and remained elevated through May, before returning to their typical levels in June and July. The SEC report also finds the costs of trading in municipal securities market increased while municipalities had limited ability to raise funds in March 2020. The stresses, however, were relieved by the direct and indirect interventions by the Federal Reserve.

- Long-term credit stresses: There are current and potential stresses in the long-term credit markets. The SEC report identifies COVID-19 shock in March to be among the worst the economy has ever experienced. This category of stresses are arguably most significant for analysis because: “i) long-term credit—e.g., residential and commercial mortgages, corporate bonds and leveraged loans, and municipal bonds—accounts for a large fraction of the $54 trillion of credit in the U.S. financial system; (ii) as a general matter, these markets are most affected by aggregate and sector-specific macroeconomic conditions and interest rates; and (iii) however, in times of stress, these markets become significantly more affected by (interconnected with) the performance of other markets, particularly including the short-term credit markets.”

- In the first and second quarter of 2020, banks booked near-historically high amounts of current and estimated future loan losses. “Because banks were well capitalized and generally were not carrying large inventories of credit-sensitive instruments, they have not experienced significant balance-sheet stresses in coping with the general economic shock.” This along with the actions taken by the Federal Reserve and the government has enhanced market stability. However, long-term exposure remains. Forbearance rates peaked at 8.55% of mortgages outstanding in June 2020. There are remaining concerns in the corporate bond market as extended COVID-19 could cause financial stress in this market. While COVID-19 has not yet appeared to impact leveraged loan and collateralized loan obligation (CLO) markets, this remains to be seen and monitored.

- According research by McKinsey & Company, there are three possible scenarios for COVID-19 impact. In the two milder scenarios, in which GDP does not recover until 2021 and 2023, the U.S. banking system as a whole is expected to withstand the damage. U.S. banks entered the pandemic crisis with a common equity tier-1 (CET1) capital ratio 12%. (note that the ratio is used as an estimate for bank’s capitalization to indicate its ability to withstand damage). In the two scenarios, the ratio is projected to fall to 10.5% and 8%–in either case the ratio would be above the minimum requirements set by regulators. This means that the banking system would maintain adequate capitalization throughout.

- In a severe scenario, in which a recession would last until 2025 or later, CET1 ratios in mature economies such as the United States are projected to fall below regulatory minimums. However, considering that U.S. banks tend to reserve for losses faster their European counterparts, McKinsey projects that U.S. banks will hit the losses sooner but also recover faster. Capital low points are expected to come in 2021 for U.S. banks. According to McKinsey estimates, U.S. banks would return to pre-crisis levels of return on equity (ROE) by 2023.

- The view is also shared by the Atlantic Council analysis, which suggests that “the system has held up.” Deliotte also projects ROE recovery to begin in 2021 (see the figure below).

REGULATORY RISKS

The last financial crisis triggered a decade regulatory reforms in the United States and globally. The focus of regulations is shifting towards financial and operational resilience, technological change and innovation, and responses to political and social pressures. Please note that, because of COVID-19, some regulations have been temporarily loosened to deal with the pandemic impacts. This section does not look at those temporary exceptions.

1). Regulatory System

- Over the last decade, two key financial regulatory reforms are Dodd-Frank Act, particularly the Volcker Rule–which “prohibits banking entities from engaging in proprietary trading or investing in or sponsoring hedge funds or private equity funds”–and Basel III, an international regulatory framework which sets minimum capital requirements for banks.

- It is important to note that there is no single U.S. regulator “tasked with monitoring and assessing the risks that these firms’ activities posed across the entire financial system.” According to a report by Congressional Research Office, “how and by whom a firm is regulated depends more on the firm’s legal status than the types of activities it is conducting. This means that a similar activity being conducted by two different types of firms can be regulated differently by different regulators.” The U.S. regulatory system is described as “fragmented, with multiple overlapping regulators and a dual state-federal regulatory system. The system evolved piecemeal, punctuated by major changes in response to various historical financial crises.”

- Deloitte describes the current trend in the regulatory system as the new age of tailoring by bank regulators. “The recent final rule by the [Federal Reserve Bank] that tailored the Enhanced Prudential Standards (EPS) for domestic and foreign holding companies marks a significant new stage in the evolution of tailoring by bank regulators—a trend that intensified under the [Trump] administration. As designed, the EPS tailoring rule fine-tunes requirements for capital, stress testing, liquidity, large exposures, and reporting based on financial metrics that serve as a proxy for a firm’s size, complexity, interconnectedness, and systemic importance.”

- For large global financial institutions, the focus continues to be on mitigating conduct risk as heightened regulatory scrutiny in that capital market persists. In the meantime, financial institutions are facing a fast approaching deadline for phase-out of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), a globally accepted benchmark rate. Note that LIBOR appears in contracts governing about $200 trillion in U.S. derivatives and other securities and an additional $67 trillion in other non-U.S.-dollar products in the United States, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). According to Deloitte’s analysis, there are two challenges. “The first significant issue is to identify and inventory contracts representing trillions of dollars in financial commitments, which may be contained in systems and formats widely dispersed across products and business areas. The next major challenge is to repaper those contracts using a new benchmark, even as suitable replacements for LIBOR are still developing.”

- As large financial institutions continue to adopt advanced technology, data security has become increasingly center of the attention of regulators. Nonetheless, data security is subject to state laws. This means that financial institutions must mitigate risk according to each state law. Whether or not the U.S. Congress will act to pass a federal law remains to be seen.

2). Costs of Compliance

- Global financial institutions are expected to spend $180.9 billion on compliance costs in 2020, according to a new report from LexisNexis Risk Solutions. Globally, the costs have increased by 7% over the past two years. The United States and Europe face the highest compliance bills, the research found. The rising costs are attributed to partly the volumes and complexity of regulations but are largely driven by higher costs of skilled labor required for compliance work.

- The U.S. and Canadian financial firms are projected to see a 33% increase in compliance costs from 2019 to 2020. In the United States alone, the LexisNexis research projects costs to be $35.2 billion in 2020. Financial crime compliance professionals in the U.S. attribute an average of 23% of financial crime compliance cost increases to the COVID-19 impact. The research also finds the followings:

- 91% reported a negative impact on customer risk profiling

- 83% reported a negative impact on sanctions screening

- 78% reported a negative impact on know your client (KYC) for account onboarding

- 74% reported a negative impact on efficient resolution of alerts

- 61% reported a negative impact on positive identification of sanctioned entities or politically exposed persons (PEPs)

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP

- As mentioned in the initial findings, there has been a shift to focus on building trust and customer relationship, particularly in the wake of the last financial crisis and a series of financial scandals by large financial institutions since then. Globally, “nine out of 10 banks are strongly interested in customer-facing ecosystems, with banks participating in a network of interlinked companies, working together to deliver value propositions to meet customers’ core needs,” according to Accenture. U.S. banks share this sentiment with their peers, as 87% say that customer-facing ecosystems initiatives will be the main driver of future value creation in the banking industry.

- After the last financial crisis, financial institutions were widely seen as a big part of the problem. However, according to McKinsey, this time around they are seen as central to the solutions. With COVID-19 pushing many to move financial transactions online or digitally, “superior customer experience means clarity and transparency, support for digital tools with which many customers are still unfamiliar, and new products and services for customers in distress.”

- For banks, investing in customer experience was an imperative before the current crisis, both from a “good business” perspective and a “good bank” perspective. These factors have become more relevant than ever now. McKinsey’s analysis of 23 publicly traded U.S. banks finds that the half with a high customer-satisfaction score delivered 55% returns to shareholders from 2009 to 2019.

Case Studies: BlackRock, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Citigroup

BLACKROCK

Please note that this section uses data from the 2019 annual report and Q3 2020 report as the annual report for 2020 has not been released yet.

- BlackRock is an investment management firm. Its revenue is driven by investment advisory, administration fees and securities lending ($11.78 billion of total revenue of $14.54 billion).

- In its annual statement, BlackRock suggests that the asset management industry continues to go through a period of consolidation, fee compression and technological transformation, at the center of its business strategy is anticipating this change and always evolving the firm from a position of strength.

- Over the last decade, investors have increasingly recognized that portfolio construction, not security selection, drives the majority of returns. Investors have increasingly sought out managers such as BlackRock that have the offerings, technology and client service capabilities to execute a whole-portfolio approach.

- Despite the current pandemic, BlackRock reports strong performance in the third quarter of 2020:

- $129 billion of quarterly total net inflows, led by continued momentum in fixed income and cash management, with positive flows across all regions, investment styles and product types.

- 7% annualized organic asset growth in the quarter and higher organic base fee growth reflect strength of diversified investment management platform, especially active equities, illiquid alternatives and strategic focus areas of iShares.

- 18% increase in revenue year-over-year reflects higher performance fees and continued organic growth.

- 17% increase in operating income year-over-year includes the impact of $83 million of product launch costs in the third quarter.

- 24% increase in diluted EPS (29% as adjusted) also reflects higher year-over-year nonoperating income and a lower diluted share count in the current quarter.

J.P. MORGAN CHASE

Please note that this section uses data from the 2019 annual report and Q3 2020 report as the annual report for 2020 has not been released yet.

- The biggest driver of the bank’s noninterest income revenue comes from asset management ($17 billion) and principal transactions ($14 billion), which is when “an adviser, acting for its own account, buys a security from, or sells a security to, the account of a client.” This is followed by investment banking fees, lending/deposit-related fees, and card income. Net interest income is $57.2 billion, up 4%, driven by continued balance sheet growth and mix as well as higher average short-term rates, partially offset by higher deposit pay rates.

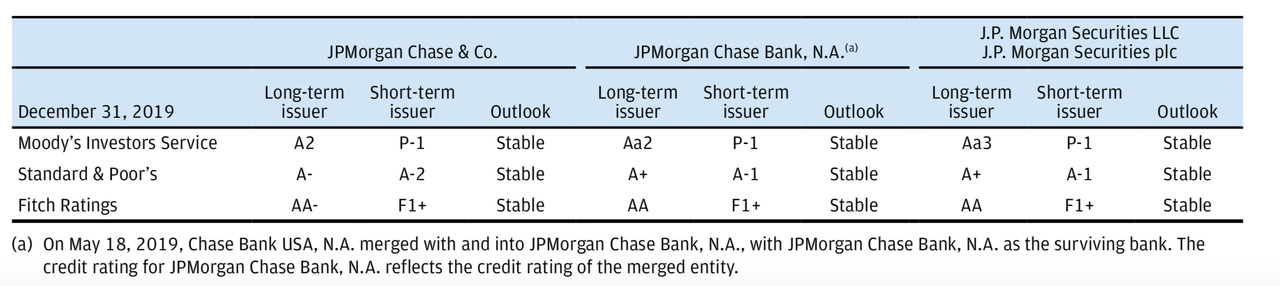

- The cost and availability of financing are influenced by credit ratings. Reductions in these ratings could have an adverse effect on the firm’s access to liquidity sources, increase the cost of funds, trigger additional collateral or funding requirements and decrease the number of investors and counterparties willing to lend to the firm. The nature and magnitude of the impact of ratings downgrades depends on numerous contractual and behavioral factors, which the firm believes are incorporated in its liquidity risk and stress testing metrics. The firm believes that it maintains sufficient liquidity to withstand a potential decrease in funding capacity due to ratings downgrades. (See the figure below credit ratings).

- In its 2020 Proxy Statement, J.P. Morgan Chase stresses its exceptional client service and operational excellence. “Guided by the Firm’s Business Principles, this year the Operating Committee deployed a Strategic Framework designed to reinforce the Firm’s drive to be complete, global, diversified and at scale, so we can best serve clients at home and across the globe. Within this framework, there is a strong focus on the technology that will be key to the Firm’s future success, including initiatives that will allow the Firm to reduce risk and fraud, upgrade customer service, make it easier to access products and services, improve underwriting and enhance resiliency.”

- In its Q3 2020 report, J.P. Morgan Chase has a ROE of 15% and an increase in average deposits of 30%. Despite the pandemic, the firm maintains a health CET1 capital ratio of 13%.

CITIGROUP

Please note that this section uses data from the 2019 annual report and Q3 2020 report as the annual report for 2020 has not been released yet.

- Citi has a strong global presence, with 47% of net revenue coming from North America, 22% coming from Asia, 17% coming from Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA), and 14% coming from Latin America.

- 2019 is the bank’s most profitable year since 2006 with earnings per share of $8.04, a 20% increase from 2018.

- According to its 2019 annual statement, the expectations of consumer and institutional clients continued to converge. Both groups want simple, seamless experiences that are not just best of bank but best in life, prompting the bank to allocate substantial resources and mindshare to exceeding its clients’ evolving expectations of engaging with Citi on their channel of choice.

- In its 2020 proxy statement, Citi suggests that it looks to “continued steady progress in the bank’s financial performance, although that will obviously be impacted by the very real challenges of continued lower interest rates; the expectations of lower global growth resulting from the Coronavirus and other factors; and the need for continued investments in key businesses, infrastructure, compliance, and controls.” Citi again achieved a successful result in the Federal Reserve’s annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR), resulting in a return of capital to common shareholders of $22.3 billion during the calendar year, while maintaining levels of capital and liquidity well in excess of minimum requirements. It also highlights that the bank took a strong leadership role on several environmental, social, and governance issues of real importance.

- In its Q3 2020 Report, revenues decreased 7% from the prior-year period, primarily reflecting lower revenues in Global Consumer Banking (GCB) and Corporate / Other, partially offset by growth in Fixed Income Markets, Investment Banking, Equity Markets and the Private Bank in the Institutional Clients Group (ICG). Net income declines 34% from the prior-year period, largely driven by the lower revenues, an increase in expenses and higher credit costs.

- The REO for Q3 2020 is 6.7%. Despite the pandemic, CET1 capital ratio remains fairly healthy at 11.8%.

Summary of Case Studies

None of the three financial institutions chose for case studies is currently experiencing financial distress. BlackRock understandably does not appear to be at risk as it is an asset management firm, not a bank; thus, it is less exposed to consumer loans (as seen in the initial findings these are areas where loan losses are most prominent). Both J.P. Morgan Chase and Citi have exposure to consumer loans. However, both still maintain capital ratios well above the minimum regulatory requirements.